AGAMENNONE – DA QUALCHE PARTE ADESSO

[AGAMEMNON – SOMEWHERE RIGHT NOW]

2003

tratto da / from Agamennone di Eschilo

con / with Massimiliano Balduzzi (il guerriero malinconico), Nenè Barini (la donna che non ha paura dei cani), Sara Corso (la donna dalle mani veloci), Piera Cristiani (la cannonata dell’avvenire), Federico Tessieri (il comandante fuori rotta), Anna Teotti (Niarulina)

regia e drammaturgia / direction and dramaturgy Anne Zénour

realizzato al / realized at Capanno di Ribatti (Toscana) nel 2003; presentato / presented tra il 2003 e il 2005 al Capanno di Ribatti, Cremona, Bologna, Siena

“La sigaretta di un carcerato ai primi piovaschi dell’autunno, l’eroe dimenticato, ormai in pensione, con le scarpe rotte… La sera ricordiamo cose perdute – un uccello malato, due versi di Porfiras, case bruciate, manifestazioni, cartelli, bandiere a mezz’asta, un antico scenario sbiadito…”

da Studio dell’ultimo ruolo di Yannis Ritsos

“A prisoner’s cigarette in the first rains of autumn, the forgotten hero, now retired, with broken shoes…. In the evening we remember lost things – a sick bird, two verses of Porfiras, burned houses, demonstrations, signs, flags at half-mast, an ancient faded scenery…”

from Study of the Last Role of Yannis Ritsos

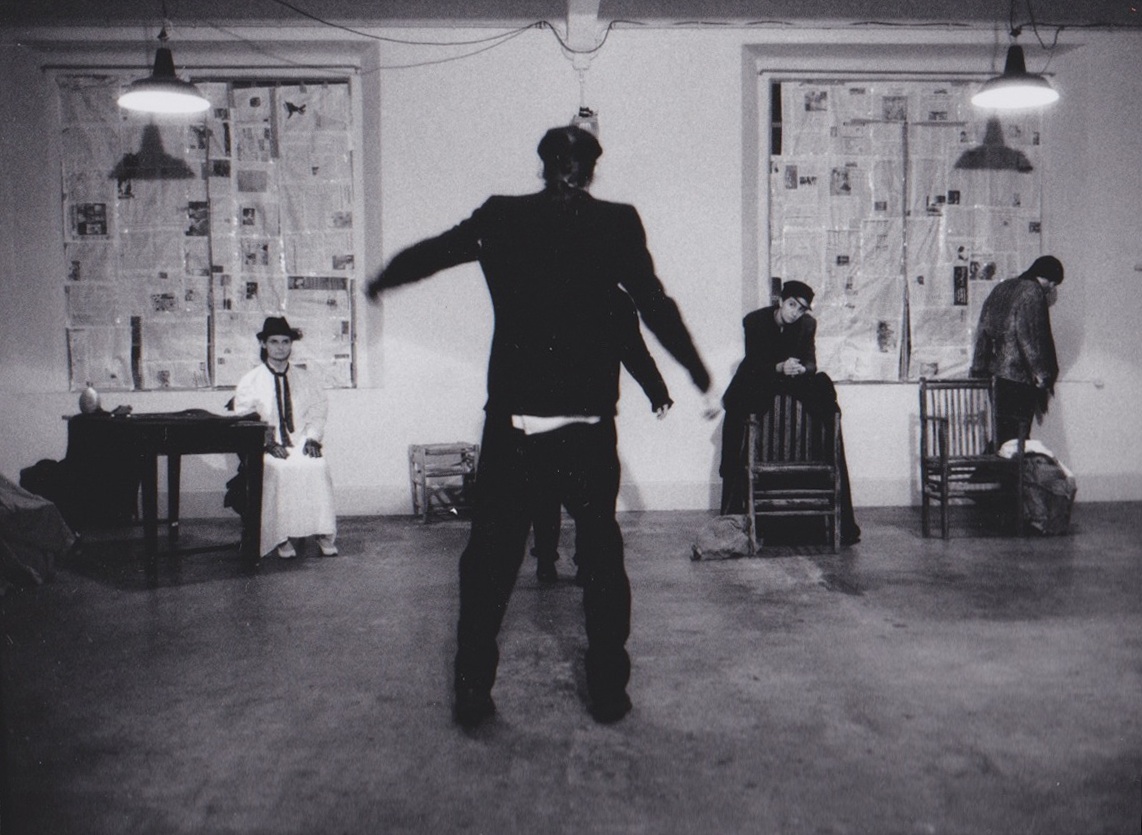

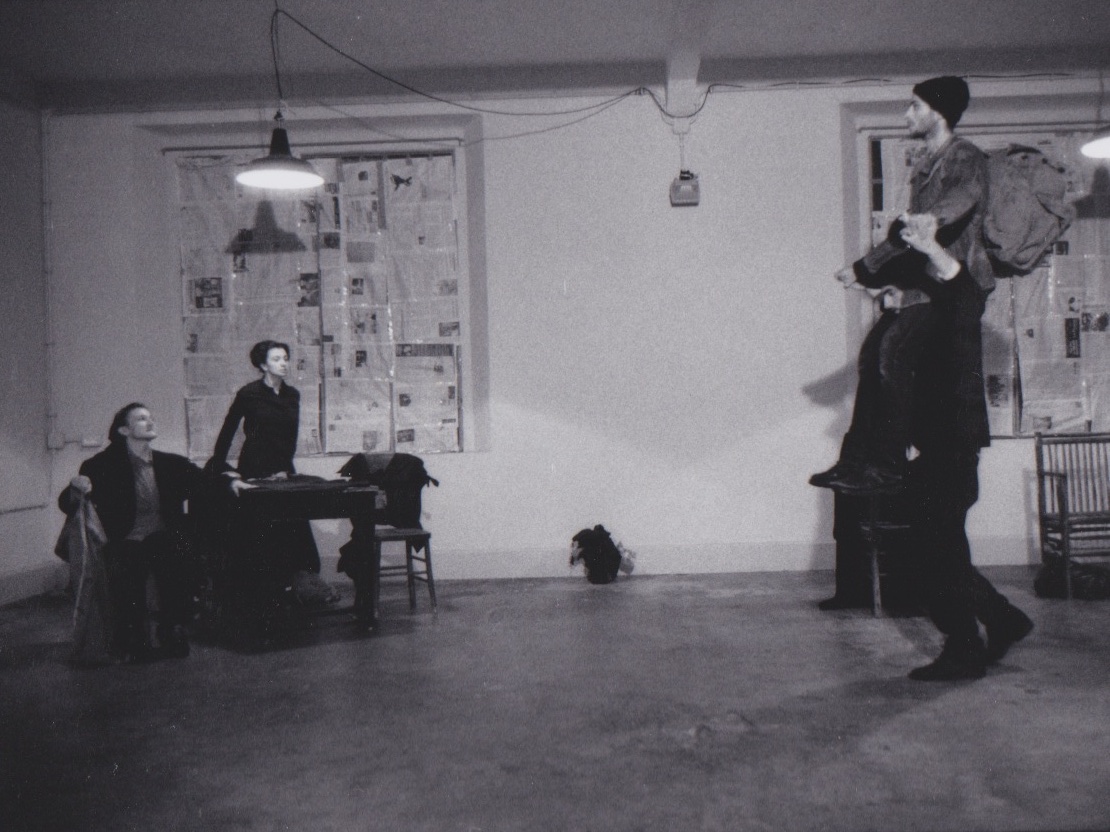

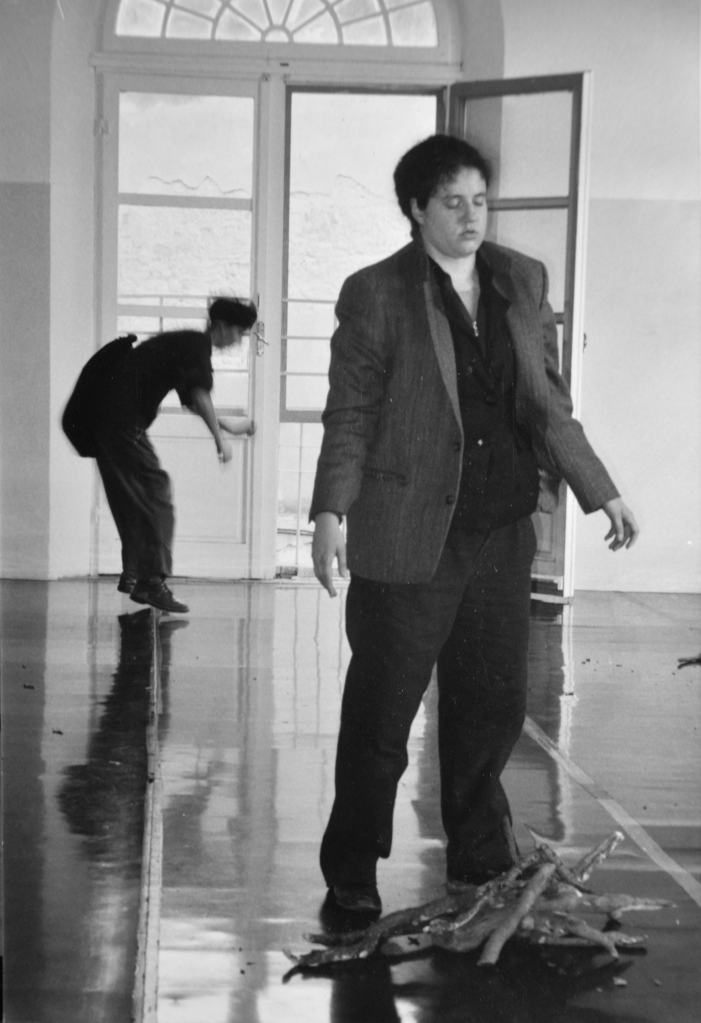

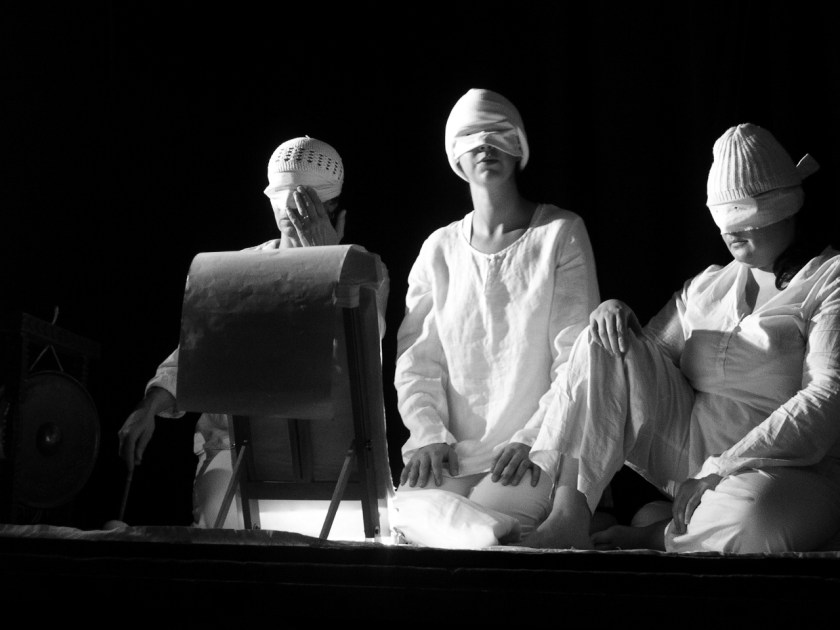

Entrano. Sono sei. Cinque adulti e una ragazzina. Sono stanchi, forse da un lungo viaggio, da una lunga erranza. Sono dei commedianti in fuga dal proprio paese, accomunati dall’esilio e dalla memoria di un tempo lontano in cui avevano recitato insieme. Si assopiscono. Uno non riesce a dormire e comincia a borbottare le parole della sentinella all’inizio dell’Agamennone di Eschilo: “Dei, vi chiedo che finisca presto questa pena…” Così, all’improvviso, le parole e gli eroi della tragedia risorgono e la vecchia recita riprende vita. Cosa rivivono attraverso questo testo che evoca continuamente i morti, le vittime della violenza e della presunzione dei potenti, l’empietà dei vincitori, “il tormento di chi è stato ucciso” che “può sempre ridestarsi…”? È un’occasione per sfogarsi, per esibirsi, per accusare qualcuno forse, e chi? I potenti della terra, Dio, uno dei compagni d’esilio?

They enter. There are six of them. Five adults and a young girl. They are tired, perhaps from a long journey, from a long wandering. They are comedians fleeing their country, united by exile and the memory of a distant time when they had acted together. They doze off. One cannot sleep and begins to mutter the words of the sentinel at the beginning of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon: “Gods, I ask that this punishment end soon…” Thus, suddenly, the words and heroes of the tragedy resurrect and the old play comes alive again. What do they revive through this text that continually evokes the dead, the victims of the violence and presumption of the powerful, the impiety of the victors, “the torment of those who have been slain” that “can always rise again…”? Is it an opportunity to vent, to perform, to accuse someone perhaps, and who? The powerful of the earth, God, one of the fellow exiles?

Hai dimenticato? Hai dimenticato quando è morto tuo padre? Hai dimenticato come è morto tuo padre?

Queste parole di un poeta coreano, le sue poesie, quelle di Yannis Ritsos e altri testi scelti singolarmente da ciascun attore (Antonio Lobo-Antunes, Etty Hillesum, Edna O’Brien, Primo Levi, Cesare Pavese, Mario Rigoni-Stern, Nuto Revelli) – testi che dicono la necessità di “non dimenticare” o evocano la situazione dei sopravvissuti a una guerra – sono stati molto importanti per avvicinarsi al testo di Eschilo, per sentirne la stupefacente attualità.

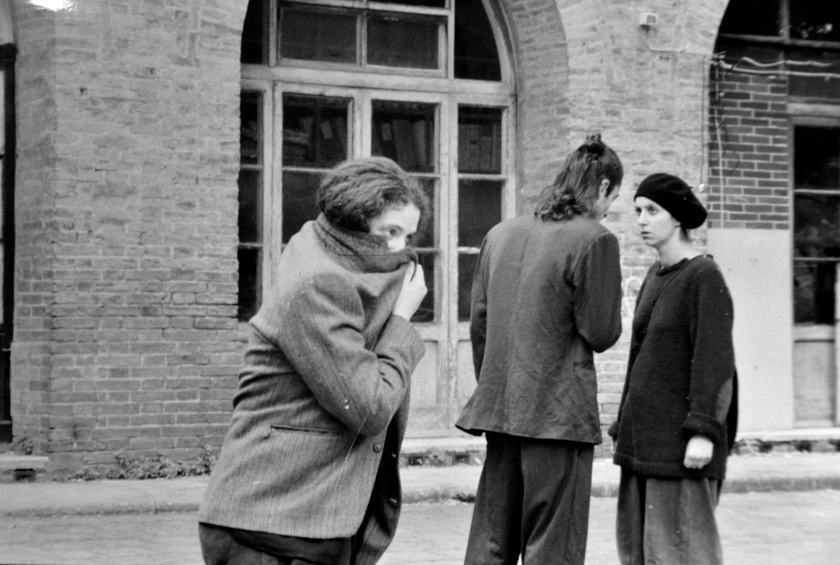

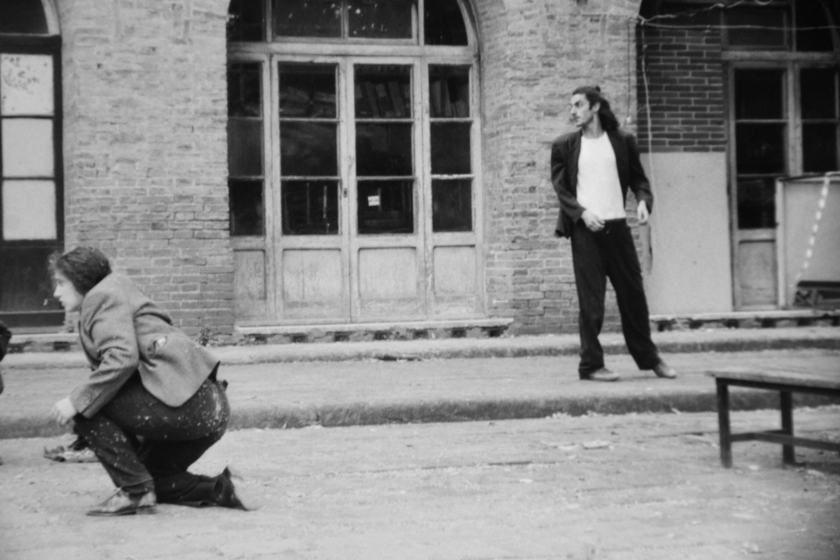

L’elaborazione dello spettacolo si è svolta su un lungo tempo in diverse tappe e ciascuna ha nutrito in modo diverso il lavoro. La prima è stata in Toscana, dove siamo stati ospitati per due mesi nella primavera del 2001. Il lavoro all’esterno è stato allora fondamentale: andare attraverso la campagna, da viandanti, da soli, o insieme, rimuginando il testo di Eschilo, correndo o camminando, attenti al minimo mutamento del paesaggio, al cielo, ai propri ritmi, sotto il sole, la pioggia, o nelle tempeste che invadevano anche la sala di lavoro attraverso le grandi aperture prima destinate a far passare l’aria per il fieno. Questo primo incontro ha permesso di tessere dei legami forti tra i membri di quel gruppo errante, di sentire poco a poco un vissuto comune, ha permesso di cercare le parole del testo che per ciascuno erano significative e collegate alla propria storia di esule. Un’altra tappa importante è stata il Teatro Polivalente Occupato di Bologna che ci ha ospitati nel 2002 e 2003: un relitto urbano in cui la situazione di questi esuli e il testo della tragedia hanno trovato altre risonanze, altrettanto forti. Importante anche perché ai cinque commedianti del gruppo iniziale si è aggiunta Niarulina, la piccola che guarda tutto, ride, piange, e illumina a suo modo il decorso della tragedia.

Have you forgotten? Have you forgotten when your father died? Have you forgotten how your father died?

These words of a Korean poet, his poems, those of Yannis Ritsos, and other texts individually chosen by each actor (Antonio Lobo-Antunes, Etty Hillesum, Edna O’Brien, Primo Levi, Cesare Pavese, Mario Rigoni-Stern, Nuto Revelli)-texts that speak of the need to “not forget” or evoke the plight of war survivors-were very important in approaching Aeschylus’ text, in feeling its astonishing relevance.

The development of the play took place over a long time in several stages, and each nourished the work in a different way. The first was in Tuscany, where we were hosted for two months in the spring of 2001. The work outside was then fundamental: going through the countryside, as wayfarers, alone, or together, mulling over the text of Aeschylus, running or walking, attentive to the slightest change in the landscape, to the sky, to one’s own rhythms, in the sun, the rain, or in the storms that invaded even the workroom through the large openings previously intended to let air through for the hay. This first meeting made it possible to weave strong bonds among the members of that wandering group, to feel little by little a common experience, allowed them to search for the words in the text that were meaningful to each and connected to their own exile story. Another important stage was the Occupied Multipurpose Theater in Bologna that hosted us in 2002 and 2003: an urban wreck in which the situation of these exiles and the text of the tragedy found other resonances, equally strong. Also important because the five comedians of the initial group were joined by Niarulina, the little girl who watches everything, laughs, cries, and illuminates in her own way the course of the tragedy.

KASPAR

2004

tratto da / from Kaspar di Peter Handke

con / with Maria Serena Bellodi (il maestro), Francesca Tamagnini (Kaspar), Piero Usberti (il piccolo violinista)

regia e drammaturgia / direction and dramaturgy Anne Zénour

realizzato a / realized at Spazio Dedalus (Cremona) e al Capanno di Ribatti (Toscana); presentato / presented a Cremona e al Capanno di Ribatti nel 2004

Sì, ho l’impressione che la mia apparizione su questa terra sia stata una caduta brutale.

Yes, I have the impression that my arrival on this earth was a brutal fall.

“La domenica di Pentecoste del 1828 fu trovato nella città di N. un adolescente che fu in seguito chiamato Kaspar Hauser. Camminava a mala pena e riusciva a pronunciare una sola frase: “Vorrei diventare un cavaliere come mio padre”. Più tardi, quando ebbe imparato a parlare, fece le seguenti dichiarazioni: per quanto si ricorda, è vissuto sempre in un buco, seduto a piedi scalzi sul pavimento: non ha mai udito un rumore, né d’uomo, né d’animale o altro. Non ha mai potuto accorgersi della differenza tra il giorno e la notte e ancor meno ha avuto occasione di vedere le belle luci del cielo. Non ha mai visto in faccia l’uomo che gli portava da mangiare e da bere. Un giorno, l’uomo l’ha issato sulle proprie spalle, e l’ha portato fuori; poi si era fatta notte fonda. Nel linguaggio di Kaspar questo “farsi notte” significava perdere i sensi, come risultò in diverse occasioni nei primi tempi del suo soggiorno a Norimberga.”

Quando Kaspar Hauser, rinchiuso in una cantina fino all’età di diciassette anni, apparve nella cittadina di Norimberga munito da uno strano biglietto di presentazione, fu accolto dal professor Daumer che gli fece da maestro in casa sua per quattro anni e notò, giorno dopo giorno, tutto quello che diceva e faceva. Cinque anni dopo il suo “arrivo nel mondo”, Kaspar fu ammazzato da uno sconosciuto probabilmente perché era diventato una presenza troppo ingombrante per quelli che l’avevano sequestrato.

“On Pentecost Sunday in 1828 a teenager was found in the town of N. who was later named Kaspar Hauser. He barely walked and could only utter one sentence: ‘I would like to become a knight like my father.’ Later, when he had learned to speak, he made the following statements: as far as he remembers, he always lived in a hole, sitting barefoot on the floor: he never heard a sound, neither of man nor of animal or anything else. He could never notice the difference between day and night, and even less had occasion to see the beautiful lights in the sky. He never saw the face of the man who brought him food and drink. One day, the man hoisted him on his own shoulders, and took him outside; then it was late at night. In Kaspar’s language this “getting dark” meant losing his senses, as turned out on several occasions in the early days of his stay in Nuremberg.”

When Kaspar Hauser, locked up in a cellar until the age of seventeen, appeared in the small town of Nuremberg armed with a strange note of introduction, he was welcomed by Professor Daumer, who tutored him in his home for four years and noticed, day after day, everything he said and did. Five years after his “arrival in the world,” Kaspar was murdered by a stranger probably because he had become too unwieldy a presence for those who had seized him.

Il testo di Handke è centrato sull’apprendimento estenuante della parola, della grammatica, delle regole da seguire per vivere in mezzo agli uomini, a cominciare da quelle che reggono il parlare e il modo stesso di pensare.

Per Kaspar, “caduto brutalmente” sulla terra – come diceva lui stesso – dotato di un’acutezza sensoriale straordinaria, come se venisse da un altro pianeta, e per il quale ogni novità è fonte di terrore, quest’apprendimento è una specie di tortura alla quale si sottomette con un fervore folle.

Il suo maestrino, che neanche lui appartiene veramente al mondo degli uomini, esegue il suo incarico, scimmiottandoli, ora con ardore, ora con noia o crudeltà.

Per una sera il maestrino apre ai curiosi lo spettacolo dei laboriosi progressi del suo allievo.

Handke’s text centers on the exhausting learning of speech, grammar, and the rules to be followed in order to live among men, beginning with those that govern speech and the very way of thinking.

For Kaspar, “brutally fallen” to earth — as he put it — endowed with extraordinary sensory acuity, as if from another planet, and for whom anything new is a source of terror, this learning is a kind of torture to which he submits with mad fervor.

His little schoolmaster, who does not really belong to the world of men either, carries out his assignment, aping them, now with ardor, now with boredom or cruelty.

For one evening, the little schoolmaster opens to the curious the spectacle of his pupil’s laborious progress.

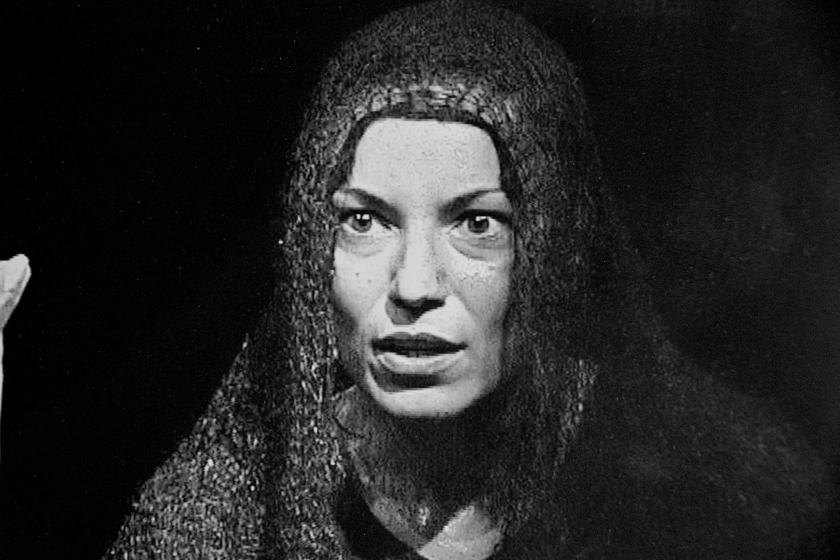

GRIDA E SUSSURRI

[SCREAMS AND WHISPERS]

2004

tratto da / from La casa di Bernarda Alba di Federico Garcìa Lorca riletto attraverso La terra de rimorso di Ernesto de Martino

con / with Massimiliano Balduzzi (la vecchia serva), Nenè Barini (una sorella), Maria Serena Bellodi (una sorella), Sara Corso (una sorella), Céline Kraus (la piccola serva), Francesca Tamagnini (una sorella), Anna Teotti (una sorella), Christophe Tostain (il visitatore)

regia e dramaturgia / direction and dramaturgy Anne Zénour

realizzato al / realized at Capanno di Ribatti (Toscana) nel 2004; presentato / presented tra il 2004 e il 2005 al Capanno di Ribatti, Siena, Modena

E che cos’hai, tu, da dimenticare?

And what do have you, you, to forget?

Lorca scrisse questo dramma nel ’36, poco tempo prima di essere ammazzato dalle squadre franchiste. In una casa vicina a quella dei suoi in campagna, viveva una donna astiosa e autoritaria che teneva sempre chiuse le figlie e le serve; Lorca si accorse che poteva sentire le loro voci scendendo in fondo a un pozzo secco situato nel suo giardino; fu così che cominciò a scrivere La casa di Bernarda Alba.

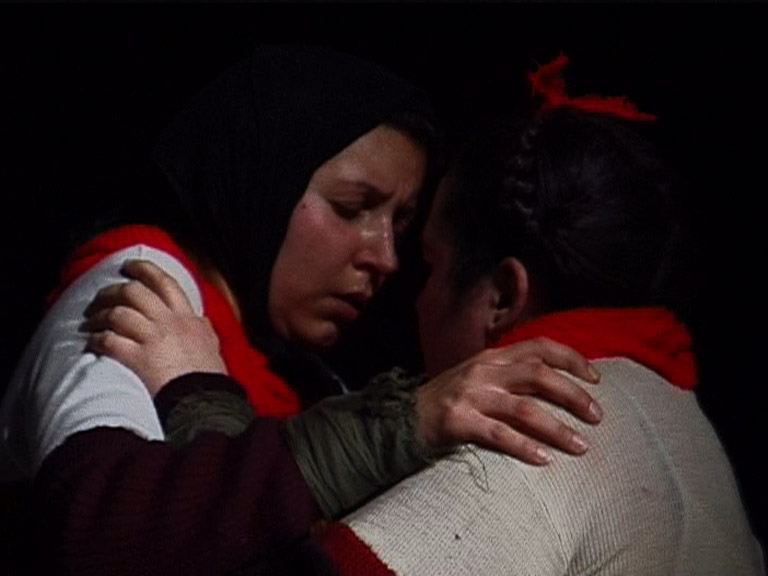

Le voci delle sorelle Alba sono risuonate per noi come voci indistinte di donne represse: ciascuna poteva a turno assumere la cattiveria, il desiderio, l’odio, la gelosia, la tristezza, o anche la voce della madre-tiranna per schiacciare le altre, o per distruggere se stessa. Pur seguendo di vicino il testo originale, abbiamo scelto una situazione di partenza diversa:

Bernarda, la madre despota, è appena morta. Le sue figlie si ritrovano dopo il funerale nella casa familiare dove risuona ancora la voce terrificante che ha per anni regolato la loro vita, negando loro per sempre qualsiasi rapporto con un uomo. Sono d’un colpo invase dai ricordi e in particolare da quello di un’altra morte: quella della sorella Adele, spinta al suicidio dalla gelosia di una di loro e dalla violenza della madre. Rievocano la lunga giornata che ha preceduto la morte della sorella, compiendo una specie di via crucis del piccolo inferno familiare, una cerimonia improvvisata nella quale sono come trascinate, a volte in modo derisorio o sognante, a volte con una voglia spudorata di esibirsi, tirando fuori i rancori e le amarezze, i sogni ormai ridicoli di amore e di piacere come, in un certo modo, le tarantate di cui parla Ernesto de Martino nel suo libro La terra del rimorso: “In tal guisa le donne di qualsiasi ceto, che il costume condannava ad un aspro regime di erotiche preclusioni, partecipavano a questi “carnevaletti di donne”; ognuna poteva così rialzare la propria sorte tanto quanto la vita l’aveva abbassata, e viveva episodi che si configuravano come il rovescio della propria esistenza.”

Il testo di Lorca è preso come una partitura corale. Non sono assegnate delle parti. Durante il tempo di questa rievocazione, ciascuna “recita” a turno l’una o l’altra sorella, o la madre, o la serva. Come nel testo originale, comincia con il lamento funebre e finisce con il suicidio. Un visitatore, l’uomo che non hanno mai avuto, muto, invisibile a loro per la maggior parte del tempo, le guarda, le ascolta, passa in mezzo a loro, le fa ballare.

Una musica funebre, suonata da una banda siciliana, scandisce in modo ossessivo questo “carnevaletto di donne”.

Lorca wrote this drama in ’36, shortly before he was murdered by the Franco squads. In a house next to his parents’ in the country, there lived an abstemious and authoritarian woman who always kept her daughters and servants locked up; Lorca realized that he could hear their voices by going down to the bottom of a dry well located in his garden; that was how he began to write The House of Bernarda Alba.

The voices of the Alba sisters resonated for us as the indistinct voices of repressed women: each could in turn take on meanness, desire, hatred, jealousy, sadness, or even the voice of the mother-tyranny to crush the others, or to destroy herself. While closely following the original text, we have chosen a different starting situation:

Bernarda, the despot mother, has just died. Her daughters find themselves after the funeral in the family home where the terrifying voice that has regulated their lives for years, forever denying them any relationship with a man, still resounds. They are suddenly invaded by memories and in particular that of another death: that of their sister Adele, driven to suicide by the jealousy of one of them and the violence of their mother. They reenact the long day that preceded their sister’s death, performing a kind of via crucis of the little family hell, an impromptu ceremony in which they are as if dragged, sometimes derisively or dreamily, sometimes with a shameless desire to perform, drawing out the grudges and bitternesses, the now ridiculous dreams of love and pleasure like, in a way, the tarantate women mentioned by Ernesto de Martino in his book La terra del rimorso: “In this way, women from all walks of life, whom custom condemned to a harsh regime of erotic foreclosures, participated in these ‘little women’s carnivals’; each could thus raise her lot as much as life had lowered it, and experienced episodes that were configured as the reverse of her own existence. “

Lorca’s text is taken as a choral score. No parts are assigned. During the time of this reenactment, each one “plays” in turn one or the other sister, or the mother, or the servant. As in the original text, it begins with a funeral lament and ends with suicide. A visitor, the man they never had, mute, invisible to them most of the time, watches them, listens to them, passes among them, makes them dance.

Funereal music, played by a Sicilian band, hauntingly punctuates this “carnival of women.”

TRAMPS (VAGABONDI)

2005

testi di / texts by Jack Kerouac, Walt Whitman, Jack London, Edgar Lee Masters

con / with Massimiliano Balduzzi, Maria Serena Bellodi, Céline Kraus, Anna Teotti

regia e drammaturgia / direction and dramaturgy Anne Zénour

realizzato alla / realized at Corte dei Miracoli (Siena); presentato / presented a Siena nel 2005

NON È NOSTRO NIENTE, SOLO IL TEMPO DI CUI GODONO COLORO CHE NON HANNO DIMORA…

NOTHING IS OURS, ONLY THE TIME ENJOYED BY THOSE WHO HAVE NO HOME…

È un luogo anonimo, forse la hall di una stazione ferroviaria, forse uno spiazzo sul bordo di una strada, forse c’è una tettoia per ripararsi dal sole o dalla pioggia, o un po’ d’acqua da qualche parte; è un luogo nel quale uno di solito aspetta qualcosa, o qualcuno, ma loro non aspettano niente di particolare, si sono fermati lì, sono lì, e poi ripartiranno.

Sono quattro: una donna uscita dall’ambiente soffocante di una cittadina di provincia, un adolescente imbevuto di Walt Whitman, un emigrato italiano più alla ricerca d’espedienti che di lavoro, e un “hobo”, uno che viaggia gratis sui tetti dei treni, ladro all’occasione.

Quattro che hanno lasciato la casa, sono partiti sulle strade, fuggendo la famiglia e il quartiere, come tanti personaggi della letteratura americana, con una voglia matta di vita nuova, di libertà, di avventure, o di autodistruzione, di farla finita con tutto, presi da una smania irrefrenabile di andare dritto davanti a sé dal nord al sud, dall’est all’ovest, sentendosi infine liberi, senza legami, senza radici, con la possibilità di sparire senza che nessuno se ne accorga.

La condizione del vagabondo, con tutto quello che costa, gode comunque del lusso della libertà, libertà dell’anima che vagabonda anch’essa, delirando, caricandosi e distruggendosi di momento in momento, ebbra di solitudine, ebbra del non fare niente, di non essere più il minuscolo ingranaggio della grande macchina produttrice. Questi quattro stanno lì, si riposano, pensano, si guardano attorno. Poco a poco emergono dei brandelli di confessioni, di racconti, monologhi a voce alta, un momento d’esplosione, quasi di festa, che dura poco, poi ripartono, ciascuno da solo, il giovane si accuccia, si addormenta, dopo aver detto a mo’ di preghiera laica uno degli ultimi poemi di Walt Whitman: “Oseresti ora tu, o anima, uscire con me verso questa regione sconosciuta…”, che è un invito ad accogliere la morte.

It is an anonymous place, perhaps the lobby of a train station, perhaps a roadside clearing, perhaps there is a canopy for shelter from the sun or rain, or some water somewhere; it is a place in which one usually waits for something, or someone, but they wait for nothing in particular, they have stopped there, they are there, and then they will leave.

There are four of them: a woman who came out of the stifling environment of a provincial town, a teenager imbued with Walt Whitman, an Italian emigrant more in search of expediency than work, and a “hobo,” someone who travels for free on the roofs of trains, a thief on occasion.

Four who have left home, set out on the roads, fleeing family and neighborhood, like so many characters in American literature, with a craving for a new life, for freedom, for adventure, or for self-destruction, to end it all, caught up in an irrepressible urge to go straight ahead from north to south, from east to west, finally feeling free, with no ties, no roots, with the possibility of disappearing without anyone noticing.

The condition of the wanderer, with all it costs, nevertheless enjoys the luxury of freedom, freedom of the soul that also wanders, delirious, charging and destroying itself from moment to moment, intoxicated with loneliness, intoxicated with doing nothing, with no longer being the tiny cog in the great producing machine. These four stand there, resting, thinking, looking around. Little by little shreds of confessions, stories, monologues in a loud voice emerge, a moment of explosion, almost of celebration, which lasts for a short time, then they start off again, each alone, the young man crouches down, falls asleep, after saying by way of secular prayer one of Walt Whitman’s last poems, “Would you now dare, O soul, to go out with me to this unknown region…,” which is an invitation to welcome death.

Questo lavoro ha il carattere di un pezzo musicale, è un’improvvisazione su una serie d’azioni precise, il cui montaggio non è predeterminato, e dipende da quello che succede tra gli attori e attorno a loro.

Il posto ideale per questa performance è un luogo pubblico, cittadino, hall di stazione, sala d’attesa, o parco pubblico, o vie interne di un condominio dove gli attori possano, almeno in un primo tempo, apparire come normali frequentatori del luogo.

This work has the character of a musical piece; it is an improvisation on a series of precise actions, the assembly of which is not predetermined, and depends on what happens between and around the actors.

The ideal place for this performance is a public, city place, station lobby, waiting room, or public park, or inner streets of an apartment building where the actors can, at least at first, appear as normal frequenters of the place.

PADRONE E SERVITORE

[MASTER AND MAN]

2005

tratto da / from Padrone e Servitore di Lev Tolstoj

con / with Massimiliano Balduzzi

regia e drammaturgia / direction and dramaturgy Anne Zénour

realizzato alla / realized at Corte dei Miracoli (Siena) nel 2005; presentato / presented a Siena, Buti e vari teatri e centri culturali in Italia

“E Vassili rammenta che c’è Nikita sdraiato sotto di lui e che è caldo e vivo e gli pare di essere lui Nikita e che Nikita sia lui e che la propia vita non sia in lui ma in Nikita. “ Nikita è vivo, dunque sono vivo anche io”, dice tra sé, pieno di esultanza.

E più nulla, da quel momento, vide, udì, e sentì in questo mondo Vassili Andrèic.”

Brechunov, il ricco mercante che è sempre riuscito nella vita, non può credere che un uomo come lui debba all’improvviso morire, perché si è smarrito una sera nella neve russa. “Non è possibile.” Abbandona la slitta e il suo servitore Nikita già mezzo congelato, fugge nella notte, gira in tondo, e torna ‘per caso’ alla slitta dove Nikita, mezzo svestito e che non fa tante storie per morire, sprofonda nel freddo della morte…

“And Vassili remembers that there is Nikita lying under him and that he is warm and alive and it seems to him that he is Nikita and that Nikita is him and that one’s own life is not in him but in Nikita. ” Nikita is alive, therefore I am alive too,” he says to himself, full of exultation.

And no more, from that moment, did he see, hear, and feel in this world Vassili Andrèic.”

Brechunov, the rich merchant who has always succeeded in life, cannot believe that a man like him should suddenly die because he got lost one night in the Russian snow. “It is not possible.” He abandons the sleigh and his servant Nikita already half-frozen, flees into the night, turns in circles, and returns ‘by accident’ to the sleigh where Nikita, half undressed and making no fuss about dying, sinks into the cold of death…

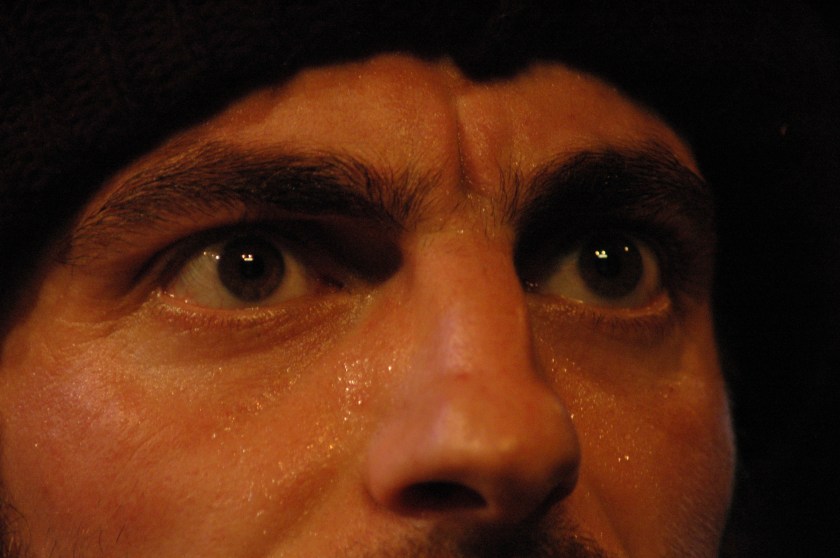

Questo racconto, come altri racconti più famosi di Tolstoj, ci parla del terrore dell’uomo davanti alla morte. La prova viene affrontata da due tipi d’uomini: il padrone, Vassili Andrèic, uomo arricchito, sicuro di sé, vanitoso, nervoso, che non teme né dio né diavolo, e il servitore, Nikita, uomo umile, paziente, e sapiente, di un sapere popolare messo a confronto continuamente con le durezze della vita. Si trovano presi, per colpa dell’avidità del padrone, che vuole raggiungere a tutti costi un villaggio per concludere un affare, in una spaventosa tempesta di neve nella steppa russa. Il racconto è come immerso in una specie di sogno dove tornano sempre gli stessi posti, è un girovagare nella neve e nella notte, tra il mondo degli uomini, familiare, caldo, illuminato, intravisto nel villaggio dove capitano più volte per sbaglio, e la tenebra biancastra del fuori, dove urlano i lupi, dove si agitano nella tempesta le piante, gli arbusti, le erbe, in preda anch’essi ai tormenti di una morte imminente.

Il mercante, sentendo avvicinarsi la morte, vede volar via, come in una fiaba, tutti i suoi averi, come se non fossero niente, meno di niente. E cosa gli resta? Solo di sdraiarsi sul suo servitore per tenergli caldo: lo fa, trova pace e muore.

Il temperamento dello scrittore russo, appassionato, impetuoso, mordente, il suo amore per la “piccola gente”, per gli animali, per le piante, per la vita quotidiana descritta nei suoi minimi particolari, la sua severità verso tutto ciò che è fatuità e ignoranza, danno a questo racconto una vitalità che non si è per niente smorzata con il tempo.

This tale, like Tolstoy’s other more famous tales, tells us about man’s terror in the face of death. The ordeal is faced by two types of men: the master, Vassili Andrèic, an enriched, self-confident, vain, nervous man, who fears neither god nor devil, and the servant, Nikita, a humble, patient, and knowledgeable man of a folk knowledge continually confronted with the harshness of life. They find themselves caught, due to the greed of the master, who wants to reach a village at all costs to close a deal, in a frightening snowstorm in the Russian steppe.

The tale is as if immersed in a kind of dream where they return to the same places again and again, it is a wandering in the snow and night, between the world of men, familiar, warm, illuminated, glimpsed in the village where they accidentally happen to happen several times, and the whitish darkness of outside, where the wolves howl, where the plants, shrubs, and grasses stir in the storm, also in the grip of the torments of imminent death.

The merchant, feeling death approaching, sees all his possessions fly away, as in a fairy tale, as if they were nothing, less than nothing. And what is left for him? Only to lie down on his servant to keep him warm: he does so, finds peace and dies.

The Russian writer’s passionate, impetuous, mordant temperament, his love for the “little people,” for animals, for plants, for everyday life described in its minutest details, his severity toward all that is fatuity and ignorance, give this tale a vitality that has not at all faded with time.

Tolstoj si è sempre colpevolizzato per la propria situazione estremamente privilegiata da grande proprietario terriero, situazione dalla quale riuscirà a staccarsi solo alla fine della vita quando scapperà letteralmente di casa, a piedi, di notte, e finirà per morire nella sala di una stazione ferroviaria a qualche chilometro da casa sua, avendo accanto solo la figlia e un’impiegata della stazione.

Scriveva nel suo diario: Il fatto di vivere in famiglia in condizioni di lusso orribilmente vergognose quando si è circondati dalla miseria, non smette di tormentarmi ogni giorno di più… Oggi ho deciso di fare quello che mi proponevo da molto tempo: andare via…Il motivo principale è questo: come gli Indù, arrivati all’età di sessanta anni, vanno nella foresta, come ogni uomo vecchio desidera consacrare gli ultimi anni della sua vita a Dio e non agli scherzi, alla maldicenza e al tennis, così io, giunto al mio settantesimo compleanno, desidero con tutte le mie forze la calma, la solitudine, e anche se non l’accordo perfetto, almeno qualche cosa di diverso da questo disaccordo stridente tra la mia vita, le mie convinzioni e la mia coscienza.

Tolstoy always blamed himself for his own extremely privileged situation as a large landowner, a situation from which he would only manage to break away at the end of his life when he literally ran away from home, on foot, at night, and ended up dying in the hall of a train station a few kilometers from his home, having only his daughter and a station clerk by his side.

She wrote in her diary: The fact that I live with my family in horribly shameful luxury when surrounded by misery, never ceases to torment me more and more each day…. Today I decided to do what I have been proposing to myself for a long time: to leave…The main reason is this: as the Hindus, having reached the age of sixty, go to the forest, as every old man wishes to consecrate the last years of his life to God and not to jokes, backbiting and tennis, so I, having reached my seventieth birthday, wish with all my might for calmness, solitude, and even if not perfect agreement, at least something other than this strident disagreement between my life, my beliefs and my conscience.

Il narratore, in veste di giovane contadino arruolato nell’esercito, trasporta gli spettatori nella steppa russa con la sua sola voce, una sedia e qualche oggetto: per lui la sedia è alternativamente il sedile della slitta, quello del padrone o quello del servitore, o una panca nella allegra casa dei contadini. Il cavallo, la strada, corrono davanti e dietro di lui e tutto attorno c’è la neve alta dove sprofonda con i suoi poveri stivali. La casa dei contadini viene evocata da un tavolo coperto da uno scialle rosso, dove il giovane accende una lampada a petrolio e prende il tè, bevendolo “alla russa”, immergendo una zolletta di zucchero nel liquido caldissimo, mentre si sentono le voci della vecchia contadina, del giovane appena sposato, dell’allegro nipote e di altri mescolarsi in un gioioso vocio. Poi di nuovo immerso nel buio e nella tempesta, fa luccicare qualche fiammifero per accendersi una sigaretta presto spenta dal vento.

The narrator, in the guise of a young peasant enlisted in the army, transports the spectators to the Russian steppe with only his voice, a chair and a few objects: for him, the chair is alternately the sled’s seat, the master’s or the servant’s seat, or a bench in the cheerful peasant house. The horse, the road, run before and behind him, and all around is the deep snow where he sinks with his poor boots. The peasants’ house is evoked by a table covered with a red shawl, where the young man lights an oil lamp and takes tea, drinking it “Russian style,” dipping a sugar cube into the very hot liquid, while the voices of the old peasant woman, the newly married young man, the cheerful nephew and others are heard mingling in a joyful hubbub. Then again plunged into darkness and storm, he shimmers a few matches to light a cigarette soon extinguished by the wind.

Non la finirai mai? Non la finirai mai di rimuginare tutto quanto?

[Will you never stop? Will you never stop mulling it all over?]

2005

ciclo di 6 letture / 6 readings

testi di / texts by Samuel Beckett

con / with Massimiliano Balduzzi, Nené Barini, Serena Bellodi, Céline Kraus, Anna Teotti e Anne Zénour

regia / direction Anne Zénour

In mancanza di sole impara a maturare nel ghiaccio

[In the lack of sun, learn to ripen in the ice]

2006

lettura / reading

poesie di / poems by Henri Michaux

con / with Céline Kraus, Anna Teotti e Anne Zénour

regia / direction Anne Zénour

ESORCISMI – ESERCIZI SELVAGGI

[EXORCISMS – WILD EXERCISES]

2006

testi tratti da opere di / texts from literary works by Henri Michaux e raccolte di poesie provenienti da diverse tradizioni / and poems from severals traditions : inuit, amerindiana, pygmee.

testi che ci hanno accompagnato / texts that accompanied us testimonianze su Hiroshima e Tchernobyl, i libri di Van Eeckout e di Luria su dei casi di afasia.

con / with Céline Krauss, Anna Teotti

luci / lights Stefano Franzoni

costumi / costumes Les Couturières

regia / direction Anne Zénour

ringraziamo / thanks to Filippo Barra, Carla Bagnoli, Luca Carli Ballola, Giada Tognazzi, Alain Volut e Gabriele Usberti

realizzato alla / realized at Corte dei Miracoli (Siena) e al Capanno di Ribatti (Toscana) nel 2006; presentato / presented tra il 2006 e il 2008 a Siena e a Segovia (Spagna)

L’esorcismo, reazione in massa,

attacco d’ariete,

è il vero poema del prigioniero.

Non ne sarà mai consigliato abbastanza

l’esercizio a chi vive suo malgrado

in dipendenza infelice

Ma avviare il motore è difficile,

solo la quasi disperazione ci riesce.

(Henri Michaux, Prove, esorcismi)

Exorcism, mass reaction,

ram attack,

is the prisoner’s true poem.

It cannot be recommended enough

the exercise to those who live despite themselves

In unhappy addiction

But starting the engine is difficult,

only near despair succeeds.

(Henri Michaux, Trials, Exorcisms)

UNO SPETTACOLO SUGLI EFFETTI DELLA VIOLENZA

E SU UN TENTATIVO DI ESORCIZZARLA

A PLAY ABOUT THE EFFECTS OF VIOLENCE

AND AN ATTEMPT TO EXORCISE IT

Qualcosa, un ricordo o una prova troppo dura, ha bloccato tutto...

(Henri Michaux, I devastati)

Something, a memory or too hard a test, blocked everything…

(Henri Michaux, The Devastated)

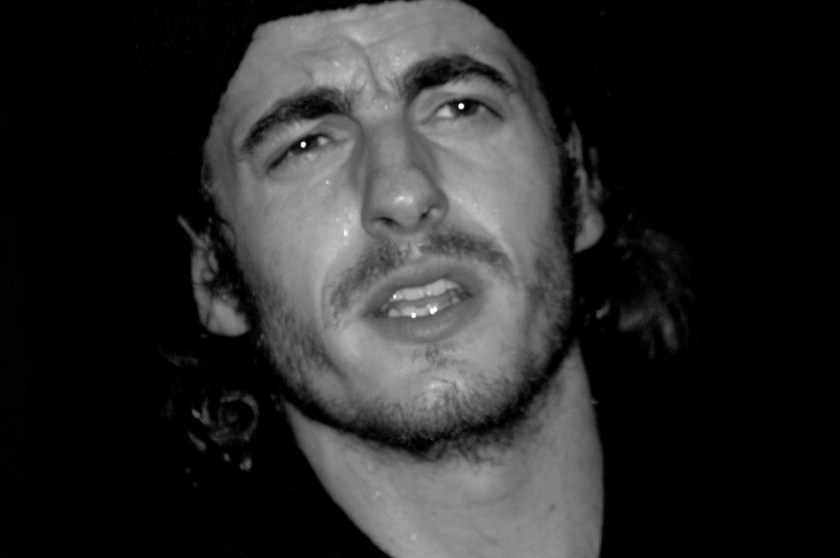

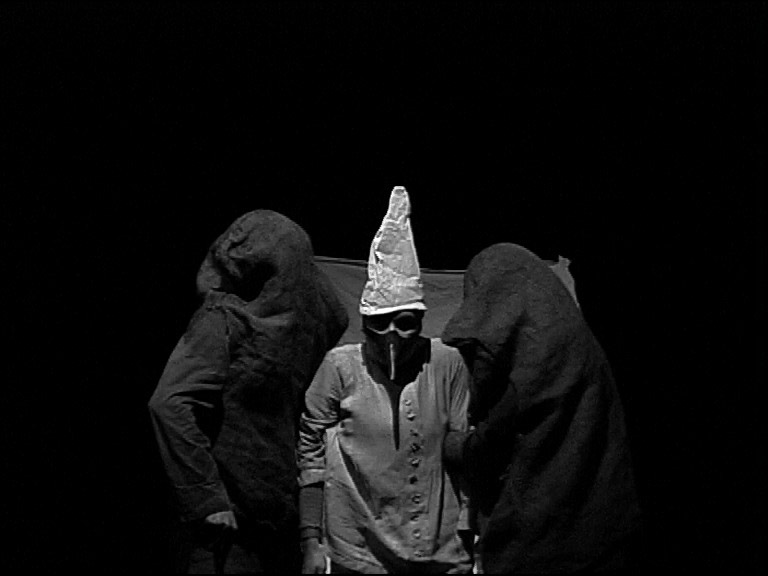

Le protagoniste dello spettacolo sono due ragazze che si ritrovano sole dopo un episodio di violenza che ha distrutto completamente il loro mondo. Per sopravivere e non essere per sempre schiacciate dal terrore, inventano una serie di esercizi, che sono come le tappe d’un tentativo di resilience. Siamo partite da due libri: Il Grande Quaderno di Agota Kristof, dove, in una paese in guerra, due gemelli costruiscono un proprio sistema di difesa e di “ governamento” del mondo che le circonda, e da Le gemelle che non parlavano di Marjorie Wallace, nel quale delle gemelle si chiudono completamente al mondo esterno per compiere i propri rituali e impadronirsi così di tutta la crudeltà latente che le circonda.

Dopo una prima fase di lavoro, la relazione tra le due ragazze, fatta di odio e di amore, ci è sembrato troppo rinchiusa su se stessa, perché quello con cui volevamo confrontarci era l’effetto che un estrema violenza può avere su un essere umano ma anche la possibilità di ritrovare un umanità, e non un ulteriore chiusura come nel caso dei gemelli e delle gemelle.

Prove, esorcismi, scritto durante la guerra, e altri scritti di Henri Michaux sono stati determinanti per condurre questa battaglia. Siamo state sostenute dal coraggio e dall’insolenza di Michaux, con i suoi modi da ‘bricoleur’ disperato e accanito, il suo lanciarsi nel buio con il rischio continuo del fallimento, per liberarsi, per scuotere la cappa di piombo che può atterrarci, paralizzarci, renderci incapaci di qualsiasi movimento – movimento che lui, Michaux, esalta: movimenti di squartamento e di esasperazione interiore, movimenti di esplosione, di rifiuto, movimenti degli scudi interiori, movimenti al posto di altri movimenti, per rinascere, per cancellare, per chiudere il becco alla memoria, per ripartire.

Da queste diverse influenze è rimasta forte la nozione di tentativo e di esercizio: un combattimento inventato passo dopo passo, mossa dopo mossa contro le forze nefaste che uno può aver interiorizzato.

È uno spettacolo fatto in gran parte di gesti, di tentativi di locuzione, di testi che tornano a brandelli, e di un rapporto fisico esacerbato tra le due protagoniste.

The protagonists of the play are two girls who find themselves alone after an episode of violence that has completely destroyed their world. To survive and not be forever crushed by terror, they invent a series of exercises, which are like the stages of an attempt at resilience. We started from two books: The Big Notebook by Agota Kristof, in which, in a country at war, twins build their own system of defense and “governing” the world around them, and from Marjorie Wallace’s The Twins Who Wouldn’t Talk, in which twins completely shut themselves off from the outside world in order to carry out their own rituals and thus seize all the latent cruelty around them.

After an initial phase of work, the relationship between the two girls, made up of hate and love, seemed to us to be too locked in on itself, because what we wanted to deal with was the effect that extreme violence can have on a human being but also the possibility of regaining a humanity, and not a further closure as in the case of the twins and the twins.

Evidence, Exorcisms, written during the war, and other writings by Henri Michaux were instrumental in leading this battle. We have been sustained by Michaux’s courage and insolence, with his desperate and dogged ‘bricoleur’ ways, his throwing himself into the dark with the constant risk of failure, to break free, to shake off the leaden cloak that can land us, paralyze us, render us incapable of any movement — movement that he, Michaux, extols: movements of quartering and inner exasperation, movements of explosion, of rejection, movements of inner shields, movements in place of other movements, to be reborn, to erase, to shut up memory, to start again.

From these different influences the notion of attempt and exercise has remained strong: an invented fight step by step, move by move against the nefarious forces one may have internalized.

It is a performance made largely of gestures, attempts at locution, texts that come back in tatters, and an exacerbated physical relationship between the two protagonists.

Sia lode ora agli uomini di fama di James Agee

[Let us now praise for famous men by James Agee]

2007

lettura / reading

con / with Massimiliano Balduzzi, Céline Kraus, Anna Teotti e Anne Zénour

regia / direction Anne Zénour

Preghiera per Cernobyl di Svetlana Alexieevic

[Prayer for Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexieevic]

2007

lettura / reading

con / with Céline Kraus, Anna Teotti e Anne Zénour

regia / direction Anne Zénour

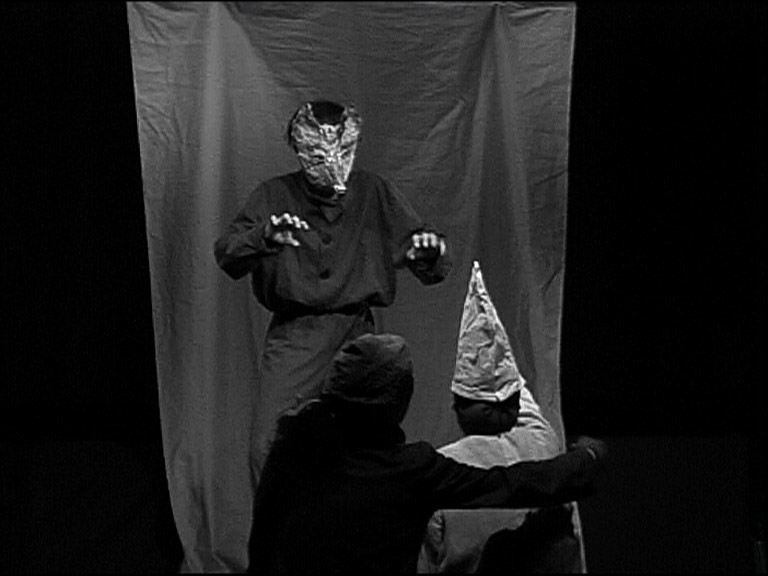

PINOCCHIO – IL BURATTINO MARAVIGLIOSO

2007

tratto da / from Le avventure di Pinocchio di Carlo Collodi

con / with Massimiliano Balduzzi, Valentina Chiefa, Marta Gabriel, Céline Kraus, Anna Teotti e Piero Usberti

luci / lights Sivia Bindi

costumi / costumes Les Couturières

regia / direction Anne Zénour

realizzato alla / realized at Corte dei Miracoli (Siena) e a Bortigiadas (Sardegna); presentato / presented a Bortigiadas e a Siena nel 2007

Chi è che mi chiama?

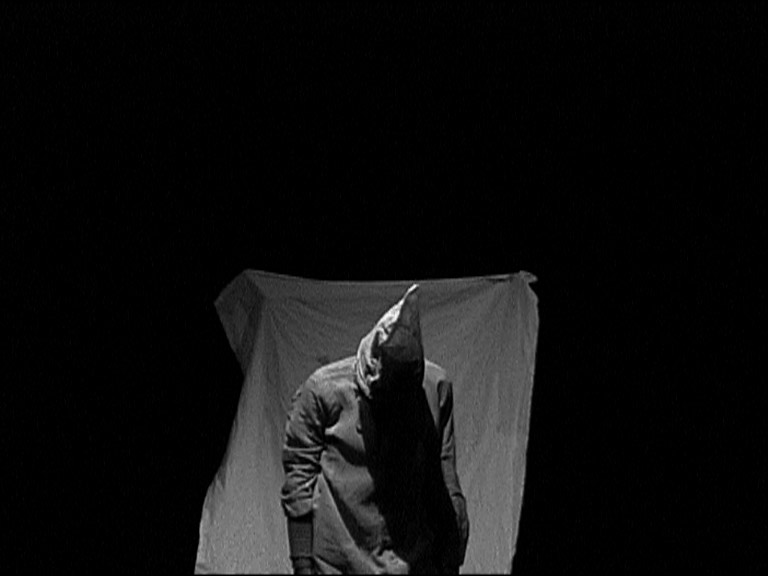

Un luogo che non riceve mai la luce del sole, come l’armadio “sempre chiuso” di Ciliegia evocato all’inizio del libro, come l’armadio dove si è installato un lontano cugino di Pinocchio, Il Monaciello di Napoli, lo “spiritello diabolico” caro a Anna Maria Ortese.

Un luogo dimenticato e nascosto, luogo consacrato delle paure e degli incubi notturni, zona intermedia tra il mondo dei vivi e quello dei morti, luogo teatrale dove gli attori hanno un carattere di apparizioni.

Là abitano gli uomini grigi, cinque figure mascherate vestite di severi vestiti e cappucci grigi. Semi nascosti negli angoli della scena, assistono all’ apparizione di un “nuovo”: il burattino Pinocchio. Sono subito incuriositi dalle sue movenze e dal suo buffissimo modo di parlare, e – chi per custodirlo, chi per derubarlo, chi per farne legna da ardere- ciascuno tenterà di impadronirsene.

Loro sono gli assassini dei nostri sogni infantili, gli adulti visti da sotto in su, con il loro carico di pulsioni e la loro voracità. Sono inquietanti e esilaranti, fanno paura e fanno ridere, e il riso raddoppia la paura.

Pinocchio li affronta con ingenuità e temerarietà, e una prodigiosa destrezza fisica, tutte qualità innate, che fanno di lui un essere tra il mago, il bambino e lo sciocco. Infatti, risorge sempre indenne e come nuovo da ogni situazione, anche se sappiamo, grazie ai suoi favolosi riepiloghi, che si ricorda tutto quel che gli è successo, travolgendone però a piacere la consequenzialità.

Pinocchio burattino solitario, “barbagianni” sfortunato, disobbediente per natura, è il nostro ridicolo eroe, gli andiamo dietro nelle sue corse folli. Bambino magico che non fa parte del nostro mondo, ma lo copia con genio, ce lo fa vedere tutto rovesciato. E da questo mondo scapperà, sparirà da un’altra parte, più misteriosa ancora della zona delle sue disavventure, non passerà dalla parte dei ragazzi per bene; e le creature dell’armadio, orfane della loro vittima, lo chiameranno in vano prima di riprendere la loro monotona erranza.

I personaggi grigi, sempre presenti sulla scena, assumono, oltre a quella di protagonisti diretti dell’azione, la funzione di un coro di voci che canta e commenta l’azione centrale, la scandisce con il suono di piccoli strumenti musicali, e quella di servi di scena, che grazie alla loro prontezza acuiscono la successione magica delle apparizioni al centro della spazio scenico.

Il testo di Collodi è un cardine dello spettacolo.

Who is calling me?

A place that never receives sunlight, like Cherry’s “always closed” closet evoked at the beginning of the book, like the closet where a distant cousin of Pinocchio’s, Il Monaciello di Napoli, the “devilish little spirit” dear to Anna Maria Ortese, has installed himself.

A forgotten and hidden place, a hallowed place of night fears and nightmares, an intermediate zone between the world of the living and the world of the dead, a theatrical place where actors have a character of apparitions.

There dwell the gray men, five masked figures dressed in severe gray suits and hoods. Semi-hidden in the corners of the stage, they witness the ‘appearance of a “new one”: the puppet Pinocchio. They are immediately intrigued by his movements and his very funny way of speaking, and-some to guard him, some to rob him, some to make firewood out of him-each will try to get hold of him.

They are the killers of our childhood dreams, the adults seen from the bottom up, with their load of urges and their voracity. They are disturbing and hilarious, scary and laughable, and laughter doubles the fear.

Pinocchio faces them with naiveté and recklessness, and prodigious physical dexterity, all innate qualities that make him a being between the magician, the child and the fool. In fact, he always rises unscathed and as new from every situation, although we know, thanks to his fabulous summaries, that he remembers everything that happened to him, yet overwhelming its consequentiality at will.

Pinocchio lonely puppet, hapless “barn owl,” disobedient by nature, is our ridiculous hero, we go after him in his mad rides. Magic child who is not part of our world, but copies it with genius, makes us see it all upside down. And from this world he will escape, he will disappear somewhere else, more mysterious still than the area of his misadventures, he will not pass over to the side of the good boys; and the creatures of the closet, orphaned of their victim, will call him in vain before resuming their monotonous wanderings.

The gray characters, always present on the stage, assume, in addition to that of direct protagonists of the action, the function of a chorus of voices singing and commenting on the central action, punctuating it with the sound of small musical instruments, and that of stage servants, whose readiness sharpens the magical succession of appearances in the center of the stage space.

Collodi’s text is a cornerstone of the show.